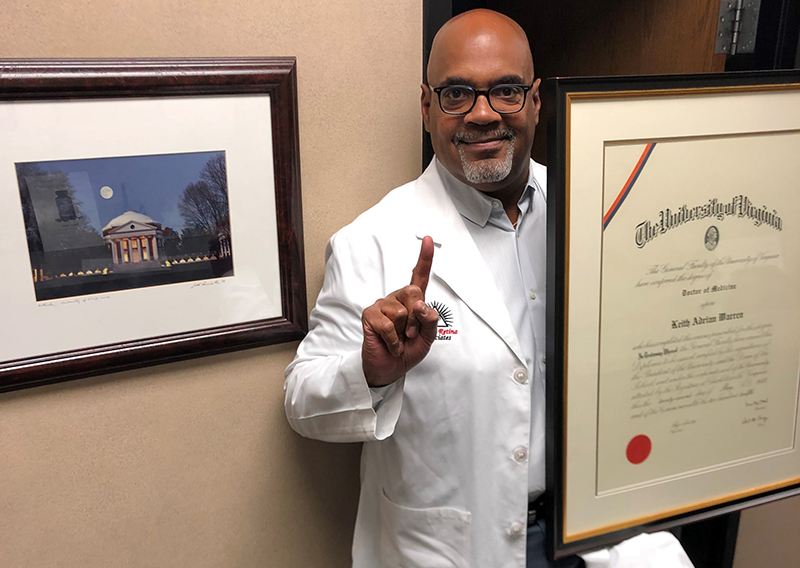

Keith Warren, MD ’88

Published: October 2021

A college basketball jersey with the number 34 hangs on the wall of Keith Warren, MD ’88’s office in Kansas City. It was the number that belonged to the University of Maryland’s Len Bias, who died tragically in 1986 from a drug-induced heart attack while Warren was in medical school. Bias was a hometown hero for Warren, who grew up in Washington, DC. “Probably one of the biggest ‘what-ifs’ ever because he was destined to just be fantastic,” he says.

Warren himself was an athlete in high school and college. He attended the University of Dayton as an undergraduate and enjoyed the independence of being away from home. During his junior year, his mother, whom he calls his hero, had eye surgery and asked her ophthalmologist to speak to her son.

“I always thought I wanted to be a doctor, but I probably was not the best student. My mom thought maybe he could talk to me, encourage me and give me some insight into a career in medicine. He was very nice, and he let me come and spend a week with him,” Warren recalls. “Watching the surgery and the patient outcomes was just astounding, and I knew at that point that ophthalmology was the career for me. As an athlete, you think you’re going to do orthopedics. That thought flew out the window once I saw ophthalmology.”

Soon after, Warren started applying to medical schools. His mother encouraged him to consider UVA because it was an excellent school and close to home. A friend in Dayton also favored UVA. “He was enamored and awestruck by the honor system. So between him and my mom, and, of course, the academic program at the university, I chose to come to UVA.”

Coming to the University of Virginia in 1979 was the best thing that ever happened to him, Warren says, because it’s where he met his wife, Carolyn. It was a bright spot in an otherwise difficult year because medical school turned out to be quite a challenge.

“I was a terrific flop. I was not very well prepared from a discipline perspective. This was the first time in my life that I failed at something I really wanted to do,” he says. “At the end of the year, they asked me to withdraw. I was extremely disappointed. When I was given an opportunity to speak with the review committee about my performance. I thought, ‘I’m usually pretty good about talking my way out.’ But it didn’t work. I went home, tail between my legs, embarrassed from the shame, but I was also smart enough to realize that they didn’t really ask me to withdraw. I asked myself to withdraw. It was my responsibility.”

Warren withdrew from medical school, but he still had an interest in medicine. He was hired as a medical technologist at the National Institutes of Health, working in the Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. There, he worked about three doors down from a doctor by the name of Anthony Fauci, whom he got to know very well. He didn’t give up on the dream of going to medical school, however, and started applying to medical schools again the following year.

At first, he didn’t reapply to UVA and focused his efforts elsewhere. And yet despite a strong work history and letters of recommendation, his applications to other schools were not accepted. After four years of rejections, his mom saw his commitment and suggested going to UVA to meet with faculty about what it would take to get back on track.

Warren did just that, meeting with Dr. James Craig and Dr. Maurice Apprey, who was the School’s newly appointed dean of minority affairs. He spoke to them about his previous experience as a medical student and what he’d done since leaving UVA.

Realizing that Warren never got a second chance before withdrawing, the faculty encouraged him to reapply. He did and was given tentative admission in 1984 based on his performance in a new pilot, the Medical Academic Enrichment Program, that was designed to help students prepare for medical school. To this day, Warren remains grateful for that opportunity. For more than 20 years, he has returned to Charlottesville to participate in the program (now called Summer Medical Leadership Program), sharing his story with students and hopefully inspiring them.

As a second-time medical student, this time Warren did very well and developed relationships with mentors who took him under their wings. “The first was Dr. Edward Hook, who was chair of the Department of Medicine. He was a champion of that summer program, and he also allowed me to participate in a summer externship with the chief resident,” he says. “The other mentor was Dr. John Jane, chair of the Department of Neurosurgery, who is my second hero. He was very encouraging and really wanted me to do neurosurgery. And I came pretty close to doing it, but I was still more passionate about ophthalmology.”

Inspired by those mentors, Warren chose to seek a career in academic medicine where he could be a “triple threat” and take care of patients, conduct research and teach. After graduating in 1988, he went on to the Medical College of Virginia for residency, followed by a retina fellowship at the prestigious University of Illinois Eye and Ear Infirmary.

As he considered an academic career, Warren considered returning to UVA or staying at the Infirmary. Instead, he chose an academic position at the University of Kansas, where he started out as an assistant professor and director of the residency program. Mirroring his UVA mentors, he was ultimately promoted to professor and chair of the Department of Ophthalmology at the University of Kansas.

Warren spent about seven years as department chair, before tiring of the time spent working through the politics of an academic institution. He also saw how the field of medicine was changing, with an increase in research opportunities in the private practice setting. Although he considered other academic opportunities or relocating outside of Kansas, Kansas was now home and he and his family wanted to stay. In 2005, Warren made the move to private practice and founded Warren Retina Associates in Overland Park. The successful practice has 10 employees and has weathered the COVID-19 pandemic, remaining open to serve patients with sight-threatening disease. He continues to lecture, participate in clinical trials and teach residents from the university.

A member of several subspecialty societies and boards, including the Board of Directors of the American Board of Ophthalmology, Warren joined the UVA Medical Alumni Association’s Board of Directors in 2020. “It’s an opportunity for me to give back to the institution that has done so much for me, my family and my career,” he says. “But also, particularly for me, I’m very happy to see that the University of Virginia is looking to expand its diversity efforts. Diversity is important because what it does is it gives people a sense of belonging. That belonging helps to foster new ideas and diversifies the university, which strengthens the community and the university. With a background in both academics and private practice, I hope to be able to offer a perspective in those areas, as well as relating to alumni that are at different stages in their career.”

In addition to serving on the board, Warren is a member of the UVA Black Medical Alumni Engagement Group, which champions diversity efforts by bringing them to the table with School of Medicine leadership, including recruiting underrepresented faculty and researchers.

As he looks ahead, Warren is excited about contributing to his profession and practicing direct patient care. He also looks forward to the day, not far from now, when his youngest daughter, a UVA graduate who is currently training at the same retina fellowship program as her dad, joins him.

While the jersey of Len Bias on his wall is a reminder of a story unfinished, Warren’s story is anything but that. “Things work out for you sometimes when you’re frustrated by your inability to move forward,” he says. “I learned a lot of important lessons about patience and persistence. But at the end of the day, what I will tell you is that you can do whatever you want to do. If you want to do it bad enough, you’ll make it happen. That’s my story. I think that’s the American story. With persistence and effort, people can achieve whatever they want. I’m living proof of that.”