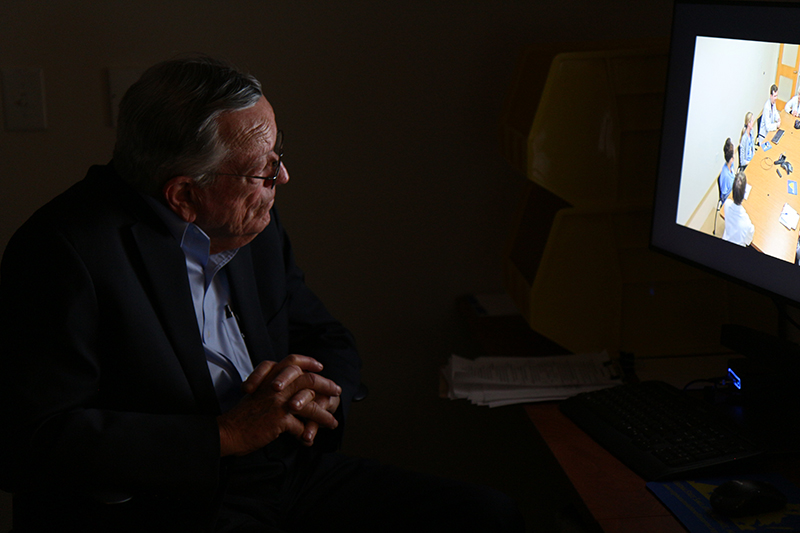

Don Richardson, MD ’62

Alumnus Don Richardson, MD ’62, observes nursing and medical students’ teamwork during an interprofessional simulation at the School of Nursing.

Story by Christine Phelan Kueter

With quickly dropping blood pressure and dwindling responsiveness, the onset of sepsis was swift and unmistakable. Nursing, medical, and pharmacy students—their voices calm even if their hearts were racing—quickly worked out the patient’s plan of care, pivoting around one another as they dialed the pharmacy, maneuvered new saline drip, and listened intently to one another.

To Don Richardson, MD ’62, who peered at the scene from behind the one-way glass of an observation room in the School of Nursing’s Clinical Simulation Learning Center during the winter of 2020, their teamwork was heartening, even as he heaved a small sigh.

The work—and the effort—had been a long time coming.

Richardson, a self-described “poor country guy,” was raised on a farm just outside of Clarksburg, West Va., and had wanted to be a doctor since age 5. He entered UVA as an undergraduate in 1954, then enrolled in medical school in 1958, graduating four years later second in his class, Phi Beta Kappa, and president of the Alpha Omega Society, the school of Medicine’s honor society.

To make ends meet, Richardson worked as a scrub nurse in UVA Hospital’s operating room, a job that, for four summers, offered him a vantage into the often fraught relationships between surgeons, medical residents, nurses, and orderlies. The experience, however, didn’t dampen his desire to become a physician, though memories of that hostile and poorly functioning medical team remained. Ultimately, Richardson would go on to become one of the region’s most respected dermatologists, with a private practice, an academic appointment, and a fierce determination to nurture the next generation of physicians.

But even as Richardson’s professional life soared, his personal life was rocked by the sudden death of his mother, schoolteacher Jesse Stewart Richardson, who died as the result of preventable medical errors. As he learned the reasons behind his mother’s untimely death—inadequate time in the ICU, an overdose of blood thinners, and poor communication between caregivers at two area hospitals—his profound sadness turned into growing rage.

He called his lawyer, ready to sue. That’s when his wife, Sheila Ammerman Richardson, a 1959 graduate of the School of Nursing, intervened and asked, “What would your mother want to do?”

“I married up,” says Richardson. “No question about it.”

First, Richardson and his sister established the Jesse Stewart Richardson Memorial Lecture at the University of Virginia School of Medicine, a series focused on medical errors “to start another level of teaching.” More recently, Richardson and his wife offered financial support to the Center for Interprofessional Collaborations at the School of Nursing to expand simulations for nursing and medical students focused on complex emergency scenarios, like the one his mother experienced.

Communication and collegial respect, Richardson insists, is key to patients’ health and wellness. And he says it’s time to change how students both are taught and how they learn.

“In the past, there was no communication between doctors and nurses, between doctors and medical students, between nurses and medical students,” explains Richardson. “Instead, there were layers of propriety. So to see the young medical students being led by the wiser nursing students, the communication—whether it’s a hand-off, or someone calling the pharmacy, or whatever—is so critically important because when you have information, you’re empowered to do the right thing.”

Research has repeatedly solidified the importance of interprofessional learning scenarios to build teamwork. As a result, growing numbers of simulations convene nursing, medical, and pharmacy students around practice scenarios like the one Richardson observed, driving home the point that practicing together yields significant benefits once students are caregivers in the real world.

“Most of the public might think this kind of thing has been going on for 50 years,” says Keith Littlewood, assistant dean for clinical skills education in the UVA School of Medicine. “But really, we’re still taking baby steps in terms of interprofessional education, but we want to be one of the leaders here. With this, we’re honoring the patients, and ourselves, and we’ll reap the benefits later on.”

For Richardson, supporting the work amplifies how important a well-functioning medical and nursing team is to patients and those who love them.

“Communication fosters successful medicine,” says Richardson. “It fosters truth being told. It decreases errors and lawsuits—it’s just worth its weight in gold, and I’m thrilled we’re doing it, even if it took a long time to get here.”

Learn about ways to support students at the School of Medicine here.